Le contenu de cette page relève de la communication marketing

Milk and asset inflation

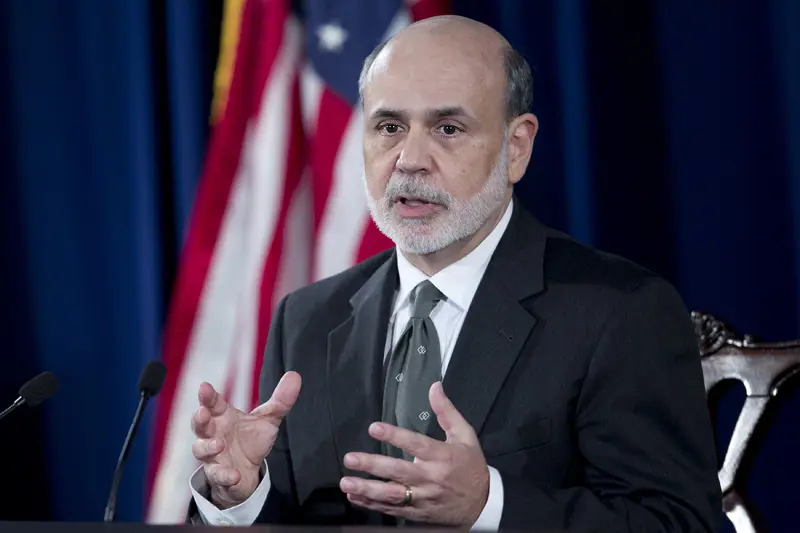

It has now been seven years since the peak of the financial crisis in the autumn of 2008, and since the then US central bank head, Ben Bernanke, initiated his first quantitative easing program (QE).

Dollar printing went into overdrive. The aim was to stimulate the US economy and avoid a repeat of the repercussions of the stock market crash of 1929. The hardships of the 1930s had the US on its knees without any artificial stimuli to get the country back on its feet.

In good Keynesian tradition, this time round governments have done whatever they can to stimulate the economy. One QE after another has seen governments pouring out billions of dollars and splurging on government bonds. In addition, the US central bank (the Fed) and other central banks have set the interest rate on bank deposits sufficiently low so as to try and enforce more lending and investments.

Based on economics textbooks, inflation in the US should have skyrocketed, but this has not been the case. Overinvestment in the commodity industry in the years before the financial crisis, new technology as well as slack in supply and labour have kept prices down. The fact that the financial services industry has been laid low in the years after the financial crisis - compounded by higher capital requirements from the government - has not exactly triggered lending muscle.

Cost cuts, mergers, share buybacks and higher dividends, together with record low interest rates have led to high inflation in the equity, bond and real estate markets. This type of inflation is not included in the official inflation figures, however.

When the rest of the world eventually followed the Federal Reserve's lead and initiated QE, inflation in the above-mentioned asset classes increased globally. The exception has been emerging markets. Here companies’ increased leverage and poor investments, with a subsequent fall in profitability, have affected equity and bond markets. Weaker exchange rates, an increased focus on costs, lower inflation and interest rates may, nonetheless, trigger asset inflation in this part of the world also.

There are seemingly many QEs – from the US in the west to Japan in the east – to thank for the last few years which have been good for equity and bond investors. Many people have failed to notice that the global economy is now growing at a decent pace. The Chinese economy still provides the best absolute growth contribution to the world economy (with the US a close second) where the transition from investing in building, construction and real estate to higher consumption is going better than many had feared. The service industry accounts for an increasingly larger share of China's GDP.

In the developed world, it now seems as though the US is the only nation which has enough momentum in the economy and job market to put the inflation target of two percent within reach.

In the rest of the civilised world, deflation remains the greatest threat to investment and economic growth. QE programs and historically low interest rates may therefore be around for some time to come. In other words, continued savings and investments in shares, bonds and property. The Fed’s long-dreaded increase of the policy rate from zero to a quarter percent – which is after all a sign that the economy is doing well - cannot disrupt this, but it may create some short-term turbulence in the capital markets.